Embodied Humors

Embodied Humoral Work for Actors read full article

The history of the body is ultimately a history of ways of inhabiting the world. – Shigehisa Kuriyama, The Expressiveness of the Body and the Divergence of Greek and Chinese Medicine (1999)

Since 2006 I have been developing Embodied Humors work: through research and a number of workshops in New York and Boston with actors and directors, I have built a training, a progression of exercises, that explores how we might physically embody the humoral theory that is central to philosophical/medical thought from the Greeks through Shakespeare and other Elizabethan playwrights. A vestige of this understanding lives on in our current language — while “humorous” has changed locations from one of many feelings to an amusing one, we still say someone is “melancholic” or “sanguine” about something, or has a “choleric personality” and I have come across “phlegmatic” in a newspaper article or two to describe someone’s actions.

But what could it mean, for example, to be someone of a melancholic temperament? As an actor, how could my very being—my physical incarnation, breath, way of seeing the world, my shape of thought—be filled with that humor? The answers are neither entirely descriptive nor psychological in the colloquial sense.

While particularly suited to practitioners of classical theater, Embodied Humors work can enlarge the performative range of all actors. The goal is to inhabit this ancient thought as living information, giving additional dimensionality to actor’s work.

Humoral Theory

To begin at the beginning: the elements from which the world is made are air, fire, water and earth; the seasons from which the year is composed are spring, summer, winter and autumn, the humours from which animals and humans are composed are yellow bile, blood, phlegm and black bile. – Galen (131-200 AD), On the Humours

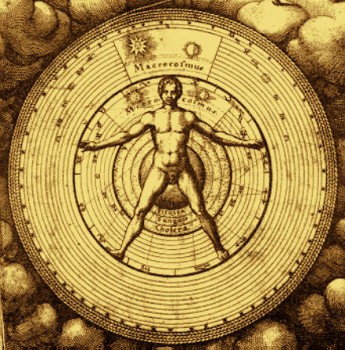

The Greeks, building on even older thought, understood the cosmos to be made of four basic energies that were seen in earth, air, fire and water. These same energies manifested in everything — the four seasons, periods of the day, food, life cycles, colors, metals, and the planets. Inside the human body the four energies were the four fluids—black bile, phlegm, blood, and yellow bile. Few people were able to maintain the ideal of a balance between the four fluids, and instead, were surfeited more by one. This was known as their humoral temperament, or “complexion” (referring to an interior condition rather than skin tone): Melancholic, Phlegmatic, Choleric, and Sanguine.

God of His goodness, that is Creator of all things, hath ordained cures for mankind…for the sustentation and health of His loving creature mankind, which is only made equally of the four elements and qualities of the same. And when any of these four abound or hath more dominion the one than the other, it constraineth the body of man to great diseases for the which the Eternal God have given…all manner of herbs to cure and heal. – Anonymous, The Great Herbal (1526)

Additionally, since humans were in direct relationship to the outside world, a person’s humoral state was seen to be influenced by diet, time of life, season of the year, and life experiences.

In her treatise Causes and Cures (c. 1150), Hildegard von Bingham referred to the energies, or elements, as being “the fabric of the human body…. They are diffused and active throughout the body…and at the same time they are spread throughout the world and work upon it.” The four energies in the elements were understood to be directly connected to the inner workings of human beings and their health, as well as their actions. Humoral theory was part of a world view in which the human being was a microcosm of a larger whole.

“All bodies are Transpirable and Trans-fluxible,” wrote Helkiah Croke, a medical practitioner, in 1615, “so open to the ayre as that it may passe and re-passe through them.” In the Embodied Humors workshops, actors develop an awareness of permeability, a constant exchange between the inside and the outside. Opening ourselves to this permeability encourages a greater responsiveness to the natural world, which continually affects what happens inside us.

Starting with strong physical expression, we proceed to feel and take on the implications of the rhythm, shape, and qualities of the correspondences. This makes us conscious of the connections between our experience, thought, and language. We have the experience of being “consumed” or “breezy” or “grounded” or “flowing.” Encounters with the elements produce a psychophysical melding. Following a workshop one student commented, “I was sad to lose my thought…when I went to air.” Another said, “I felt moved around as water.” They were identifying with the element, and were able to articulate psychological responses from there.

In Embodied Humor work we reconstruct a worldview through which we may then create characters’ actions, thoughts, and traits. We add depth to characterization, providing tools for discovering the rhythm, density, thought pattern and direction of a character, and enhancing what the actor will develop in rehearsal. Though contemporary audiences may not have knowledge of the humoral system, they will experience actors’ embodied connection to the text and character as they communicate a classical understanding of the world.

And these same thoughts people this little world,

In humours like the people of this world,

For no thought is contented. – Shakespeare, Richard II (1597)

Playwrights in both the classical and Elizabethan periods shared with their audiences a knowledge of and belief in the humoral system. Characters’ actions were governed by the flow of their humoral bias; natural phenomena could also reflect the inner world of a character. These details contributed to the audience’s understanding and experience of the play. “Yet from the same winds still/These blasts of soul hold her,” Sophocles writes of Antigone: more than a metaphor, the wind is the same — the external winds mirror the blasts of her soul.

© Merry Conway, 2011. All rights reserved

read full article